The shuttle arrived at our house at 4 AM to take us to the airport for an early morning American Airlines flight to LA. After a brief layover there, we boarded our flight to New Orleans, where we touched down as scheduled just before 4 PM local time. We took a cab from the airport to our home for the week, the Auld Sweet Olive, a B&B in Faubourg Marigny.

The Sweet Olive is charming. The building, a converted residence, dates from 1846. The Marigny neighborhood was formed in 1805, when Bernard de Marigny subdivided his plantation. The neighborhood became home to immigrants and free persons of color.

Our host, Jessica, was a delight and made us feel at home right away. Based on her recommendations for nearby restaurants, we walked to Frenchmen Street to have dinner at The Praline Connection. Wanting to get our first taste of local cuisine, we ordered filè gumbo, jambalaya with a side of collard greens, and crawfish etouffee. The gumbo, in particular, was excellent, with a dark full-of-flavor broth, not as thick and creamy as we had assumed gumbo would be.

We woke up to a beautiful, cool, sunny morning on Thursday, our first full day in New Orleans. As we walked through the neighborhood, we were impressed by the creole cottage architecture and how many of the houses have been restored and painted in bright colors. The small homes feature tall windows and balconies. Everywhere, the sidewalk paving is broken up and uneven.

Our walk brought us to Jackson Square, the heart of the French Quarter. Our plan for the morning was a guided walking tour of the historic buildings surrounding the square. We were about a half-hour early, and across the street, a long line had already gathered in front of the Café du Monde. Although I am usually put off by long lines, we got in line anyway. The line moved pretty quickly, and we were sitting at a table in the open-air café within about 10 minutes. We ordered coffee (a daring chicory coffee au lait for me and no-nonsense black coffee for my wife) and, of course, the requisite beignets. Beignets are a deep-fried light pastry—imagine a little pillow-shaped doughnut–with a snowfall of powdered sugar sprinkled on top. They arrived, still warm and scandalously delicious. The coffee could have been hotter, though.

We joined the group gathered for the 10 AM walking tour offered by the Friends of the Cabildo. Suzanne Stone, our tour guide, was great, filling us in about the early history of New Orleans with its French, Spanish and British influences. We enjoyed a 2 ½ hour tour. The time went quickly and the history was fascinating. Too much to absorb, really, but it was a good primer on what made New Orleans the city that it is today. For us, this historical tour was a great place to begin our visit, as it set the stage for a lot we were to see in the days ahead. What drew us to New Orleans was our interest in learning about the history, the architecture and the culture of the place, and this tour touched on all of that.

We had lunch at The Gumbo Shop, where we sampled their version of gumbo, which we felt was not as good as what we had the night before. I had a blackened fish salad. The food was good but not outstanding.

After lunch, we toured the Cabildo. The Cabildo was built in 1795 during the time that New Orleans was under Spanish rule (“cabildo” can be translated as “town hall”). It was the seat of local government until 1853. The Louisiana Purchase was completed with ceremonies held there in 1803. Later, between 1868 and 1910, the Louisiana Supreme Court occupied the Cabildo, and the Plessy v. Ferguson case was heard there in 1892 before the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896.

The exhibits at the Cabildo trace the history of New Orleans through the cultures of the native people and early colonial Louisiana, the War of 1812 Battle of New Orleans, plantation life, the Civil War and reconstruction. It was after 4 PM when we left the Cabildo, and we had just enough time to tour the 1850 House Museum adjacent to the gift shop that was closing at 4:30. The 1850 House is located in the Lower Pontalba Building, designed and built by the Baroness Pontalba as row-houses for the upper class. The house has been restored and decorated with period furnishings. Up a gorgeous curving staircase, we were able to see the parlor and grand dining room. The third floor bedrooms were closed.

We were feeling pretty fatigued, and so we decided to walk back to the Sweet Olive by way of the French Market, a hodge-podge of shops and flea-market vendors. It was crowded, and we saw nothing there that we wanted to buy.

Back at the Sweet Olive, we consulted our host’s list of local restaurants and decided to take a break from creole food. We ended up at Sukho Thai, which turned out to be quite good. We shared kaffir lime chicken curry and cashew chicken. The meal hit the spot for us, and we left with a serving of chocolate lava cake with blueberries to enjoy back in our room.

On Friday, I started the day with a short walk by myself to find the historical monument marking to place where Homer Plessy was arrested in 1892 for attempting to ride a train car in violation of the Louisiana Separate Car Act. The arrest was used as a test case staged by the Committee of Citizens, a group of prominent New Orleanians opposed to the law. The incident eventually led to the Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson, which infamously ruled against Plessy, sanctioning the notion of “separate but equal.” This segregationist argument was upheld as constitutional until the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. The Plessy monument—erected by descendants of both Plessy and Ferguson—is less than eight blocks away from the Sweet Olive at the corner of Royal and Press streets.

When I got back to the Sweet Olive, we took the streetcars to get to Lee Circle and the National World War II Museum. This very impressive, monumental museum was started in 2000 and is the official World War II museum of the United States. It is located in New Orleans because that is where the Higgins landing craft were manufactured. These vessels were critical to the successful D-Day landings on the Normandy coast. President Eisenhower (who, as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, led the D-Day invasion) said:

“Andrew Jackson Higgins is the man who won the war for us. Without Higgins designed boats that could land over open beaches the whole strategy of the war would have to be rethought.”

More than 20,000 boats were built in New Orleans during the war. In 1943, Higgens-designed craft made up 92% of the entire U.S. Navy.

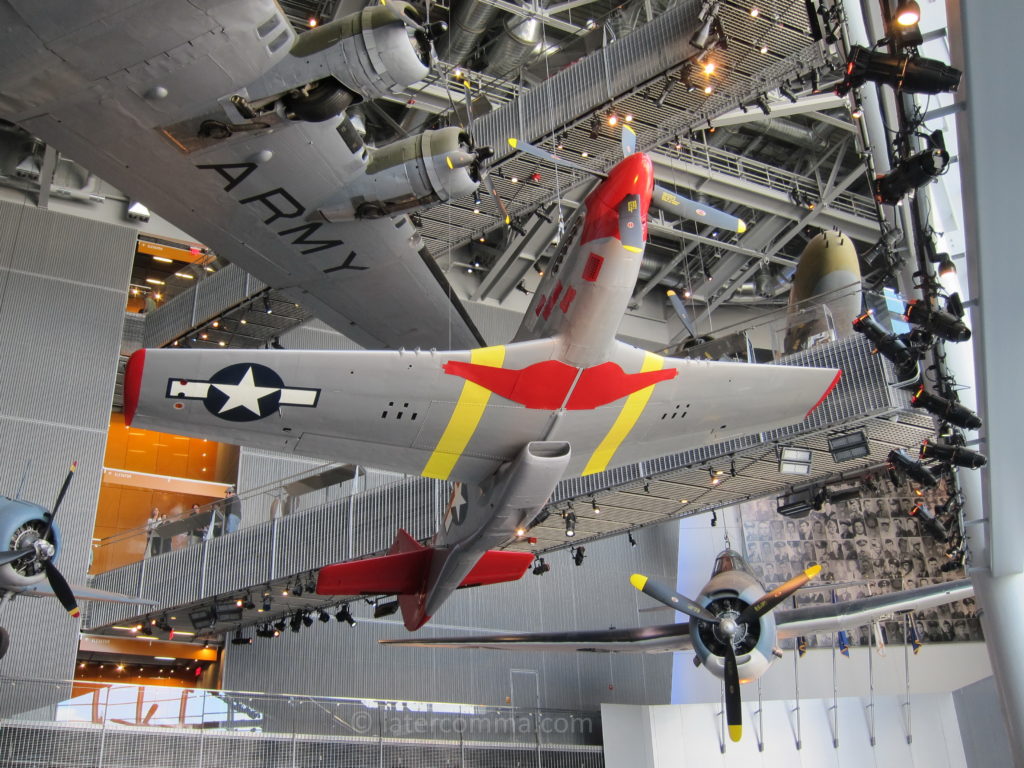

The WWII Museum is a major tourist attraction in New Orleans, and on the day of our visit we stood in line at least a half-hour for tickets—but it is a very well designed, modern museum. We started our tour with the movie, Beyond All Boundaries, a large-screen, multi-media experience (your seats vibrate when bombs go off). Anyone planning a visit to the museum should not miss this movie. The exhibits are divided into two tracks corresponding to the European and Pacific war theaters. We toured the Road to Berlin exhibits first then left the museum about one o’clock to go to lunch at Cochon, about three blocks away, where we sampled oyster stew and pork cheeks. We returned to the museum to see the Pacific theater exhibits—Road to Tokyo—as well as a separate building that contained tanks and airplanes.

Altogether, we spent six hours at the museum, and we left behind a lot that we missed, didn’t have time for, or saw but simply could not absorb. If we return to New Orleans, we will likely return to this amazing and important museum.

Because the WWII Museum took up so much of our day, we dropped our plan to visit the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and the Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, both of which are located nearby. Instead, we took a very crowded streetcar back to the French Quarter and walked down Bourbon Street.

There is a certain kind of craziness going on along Bourbon Street at any hour of the day. We briefly stopped at the New Orleans Musical Legends Park, which in reality is not a “park” at all but rather an open-air bar with statues of various New Orleans musicians—prominently Pete Fountain, Al Hirt and Fats Domino. Although we sat on a stone wall for a few minutes there and listened to the band that was playing, there is not much about Bourbon Street that attracted us.

We narrowed our dinner search to three French Quarter restaurants and eventually decided on the Café Amelie for what turned out to be, in retrospect, our best and most memorable dinner in New Orleans. We dined at a courtyard table. Brad, our waiter, was marvelous. I had an Irish Channel Stout, in honor of St. Patrick’s Day. We shared seared ahi tuna and salmon entrees. Both were delicious. We shared an order of their Doberge Cake (nine layers of cake and lemon dessert pudding) to conclude the meal.

We walked back toward the Sweet Olive along Royal Street because we knew that the Irish Club Parade was scheduled to be happening that night, coming from the east on Royal through Marigny. We saw no sign of the parade until we reached Frenchmen Street, where the parade was turning off of Royal onto Frenchmen Street. The marchers were tossing out beads and other “throws” to the crowd while parade vehicles were blaring an assortment of loud music to get the people dancing in the street. We continued along Royal, stopping at several places while my wife began collecting beads and kisses from strange men. Even I got a string of beads or two, but, alas, no kisses from strange women.

We were just getting into the parade spirit, when my wife tripped on a slab of heaved up pavement and went down, crashing into a bicycle that was tethered to a pole on the sidewalk. That was the end of our parade watching. One wrist was skinned and bleeding, both were throbbing with pain, and she felt dizzy and nauseous.

We walked back to the Sweet Olive as quickly as we could. We cleaned her wound and performed a little first aid with a band aid and some ice. I called our host, who directed us to the first aid supplies, ice packs and extra towels. My wife hoped to be without pain by the morning, but by 4 AM, there was no doubt that there was something seriously wrong with her right wrist.

We cancelled our scheduled guided tour of the Garden District and got to an urgent care clinic via taxicab. There was nothing within walking distance. The facility refused to see my wife without a photo ID, and then they rejected her insurance because they could not reach her insurance carrier by phone to confirm that we were fully covered for out-of-state, non-emergency-room care. Ultimately we agreed to pay cash.

A nurse practitioner examined my wife’s wrist. X-rays were taken (for an additional charge to our credit-card), confirming a fractured radius bone. A high-tech fabric splint was applied (cash or check only, no credit cards accepted), and my wife immediately began to feel less pain in her wrist. A taxi whisked us back to the Sweet Olive.

We conferred about our respective energy levels and decided to resume our touristy activities, beginning with a walk back to the French Quarter and lunch at Tujague’s, which has been located for 160 years across from the French Market on Decatur Street. We had turtle soup and a fried-oyster po’ boy. Both were superb.

After lunch, we decided to take a self-guided walking tour of the Algiers Point neighborhood. The Riverfront Streetcar took us to Canal Street and the ferry terminal. A short, 10-minute ferry ride gave us a view of St. Louis Cathedral from the Mississippi. Algiers Point was like visiting a different city, quiet and no tourists on the streets. We admired several old homes and other structures, including what once was a tiny Gulf gas station.

After an hour or so, we caught the ferry back to Canal Street. It was nice to be on the water, if only briefly, to remind ourselves of the importance of the Mississippi River to the history of the city.

We took the Riverfront Streetcar to the end of the line at the French Market, and decided to walk back to the Sweet Olive for a little downtime. That night we went to the Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro for dinner: blackened redfish and redfish Marigny (redfish with a creamy creole sauce with shrimp). We lingered on Frenchmen Street after dinner, catching the sounds of different bands through the open doors of the bars that line both sides of the street.

The next day, Sunday, we made our way to the Garden District via streetcars. We followed a self-guided walking tour of the magnificent homes in the neighborhood around Lafayette Cemetery. After an hour or so, we stopped in for lunch at the Gracious Bakery and Café on St. Charles Avenue and Sixth Street: a barley arugula salad and a meatloaf sandwich.

After lunch, we took the St. Charles Streetcar back to Canal Street and walked along Royal to the Historic New Orleans Collection, where we took a tour of the restored residence and museum. The beautiful interior courtyard is an example of the Spanish influence on French Quarter architecture. General Lewis Kemper Williams and his wife Leila lived in the residence between 1946 and 1963. The Williams accumulated a large collection of artifacts important to the history of New Orleans. Their philanthropy and vision is credited with preserving the character of the French Quarter—the old buildings and European atmosphere that people come from all over the world to see.

We ambled on toward Jackson Square, taking in the street life of the French Quarter. We considered going to the show at Preservation Hall on St. Peter Street. The place was closed when we walked up to the door around four o’clock. The first show was at 6 PM, and their website advised arriving 30 minutes before the show for first-come, first-served seating.

In the meantime, we walked to the Louisiana Loom Works on Chartres Street. I know nothing about weaving, but my wife engaged the owner in discussing the merits of the different looms in the shop, which included Cranbrook and Newcomb—names that were a foreign language to me. Also resident in the shop were five supremely contented cats, who all seemed oblivious of our presence.

The Preservation Hall website was unclear about whether dinner was available there—and I was getting hungry. The website also mentioned that photo ID was needed—and my wife did not have hers. We circled back to Preservation Hall to try to get more information, but by 4:30, there were already people waiting in a line that stretched halfway down the block.

We did not feel like standing in line for an hour and a half, and so we turned our thoughts to choosing a spot for dinner. We stopped in at the Petite Amelie and discussed restaurant options over some cold drinks. A local couple, overhearing our conversation, came to our table to offer their restaurant suggestions. Southern hospitality. Based on their recommendations, we narrowed our list, and eventually we chose to have dinner at Mona Lisa on Royal. It was a delightful, casual Italian dinner (thank you, mystery couple!) of eggplant parmesan and Shrimp Fra Diavolo (shrimp sautéed in brandy in a spicy red creole sauce over linguini).

The next day, walked to Louis Armstrong Park in the morning. We enjoyed the sculptures of musicians—Sidney Bechet, Louis Armstrong, Mahalia Jackson, Buddy Bolden and others—as we walked through the grounds. I had hoped that someone would be playing music in Congo Square, but nothing was happening there on a Monday morning.

We left the park and turned back toward the French Quarter, reaching the Hermann-Grima House on St. Louis Street, where we tagged on to a guided tour that had just started. The Federal style house, courtyard, work rooms and slave quarters comprise a restored mansion, circa 1830. We got to see the parlor and dining room, a library room and a children’s room on the first floor. Unfortunately for us, the second floor of the residence was closed for renovation of the exhibits there. The house did not have indoor plumbing. Bathwater was fetched in buckets by slaves, and the copper tub was tipped out into the alley when bathing was done. The kitchen was separated from the living quarters, with cooking done mostly over an open hearth in a workroom located off the courtyard. Other workrooms bordered one side of the courtyard near the slave quarters, including the laundry room and the wine room (where wine was drained from barrels into recycled glass bottles for presentation at the dinner table). A stable for the carriage horses was added when the Grimas lived in the house. The stable is still intact and features 20”-wide cypress boards framing the stalls.

Samuel Hermann emigrated from Germany in 1804 and worked as an agent and broker for plantation owners. His wife, Marie, was the daughter of a lumber mill owner. After a financial panic triggered by the collapse of the English cotton market, Hermann lost his fortune and declared bankruptcy, and his lawyer, Felix Grima bought the house and moved in in 1844. The house remained in the Grima family until 1921.

Later that afternoon we toured the Gallier House, an ornately decorated home with its Rococo Revival double parlor. New Orleans architect James Gallier, Jr., designed the house on Royal Street to be his personal residence. Gallier and his wife, Josephine, moved into the house in 1860. He died eight years later, probably from yellow fever. The Galliers had four daughters, who continued to live in the house after their parents passed away.

The Victorian era furnishings throughout the restored house closely matched a detailed inventory that was compiled at the time of Gallier’s death in 1868. The house has an indoor kitchen with a cast-iron stove. Other modern conveniences of the time included an innovative ventilation system and an indoor bathroom complete with flush toilet and hot and cold running water.

When we were done with the tour of Gallier House, we walked back to the Sweet Olive for tea on the patio. Following a New Orleans Monday dinner tradition, we wanted to have red beans and rice, and we took the short walk back to Frenchmen Street and The Praline Connection, where we had dined on our first night. We had chicken (baked and fried) with our red beans. We were not disappointed; the food was great.

As we were dining a street band started playing on the corner across the street. After dinner, we stood on the sidewalk and watched the band for a while. They were mostly high-school or younger guys playing an assortment of brass instruments and drums. They were entertaining and drew quite a crowd.

We knew that we were missing out on the evening music scene, but we faced the fact that after a full day of sight-seeing, the idea of staying out past midnight in a crowded bar—probably standing most of the time—did not appeal to us. If we ever come back to New Orleans and want a taste of the nightlife, we will plan a lazy day so that we can rest up for an evening adventure.

On Tuesday morning, we took the Number 91 bus to Beauregard Circle and walked to the New Orleans Museum of Art, located in 1,300-acre City Park. The museum displays artworks from many parts of the world, ranging from Old Dutch masters to Native American designs and including modern and contemporary art along with works from Africa, Japan and the Pacific.

One room featured Gulf Coast artists, including paintings of marshlands, images of landscapes that no longer exist, that have been worn away by coastal erosion.

The featured exhibit displayed art and artifacts from 18th Century Venice. Many of the paintings were amazingly detailed city-scapes, and it struck me that these paintings preserved images of Venetian life in that era, much as I have been capturing digital images of New Orleans city-scapes all this week.

Outside next to the art museum is the Besthoff Sculpture Garden. We spent a half-hour or so walking through the sculpture garden before we left to catch the streetcar that would take us back to the French Quarter.

We rode the Canal Streetcar to the last stop and then took the Riverfront Streetcar to the Dumaine Street stop.

We walked to the Presbytère, a building that flanks St. Louis Cathedral and mirrors the Cabildo, which stands on the other side.

Construction of the Presbytère started in 1791, but the second floor was not completed until 1813. The mansard roof was added in 1847, topped off with a cupola, which was blown off in a hurricane in 1915 and not replaced until 2005. The structure was called the Presbytère because it was built on the site of a residence for Capuchin monks, although the building was never used as a religious residence.

Currently, the Presbytère is part of the Louisiana State Museum system. We toured its exhibits on Hurricane Katrina and Mardi Gras until we were invited to leave shortly after closing time at 4:30.

For our final dinner in New Orleans, we chose Irene’s Cuisine, an excellent restaurant on St. Philip Street. We were close to the front of the line when the restaurant opened for dinner just after 5 PM. The restaurant was especially crowded that night because of a St. Joseph’s Day event, but we were seated quickly at a small table—near the kitchen, but also near a piano where a musician showed up to serenade us. The food was wonderful and our server was very efficient. To end the meal, we shared an order of cheesecake and a cup of fresh-brewed decaf. The cheesecake won the prize for the best dessert of the week.

On our last day in New Orleans, our late afternoon flight gave us bonus time to enjoy the morning in the French Quarter. We walked down Frenchmen Street to the Old U.S. Mint, where there is a jazz museum that features photographs, autobiographical writings and artifacts from Louis Armstrong’s remarkable career. The exhibit also includes a piano that belonged to Fats Domino, completely restored after being destroyed by Katrina. The Mint also has an exhibit featuring artwork by self-taught local artists, and there is an exhibit about the mint itself.

Construction of the red brick Greek Revival style structure began in 1835 and was completed in 1838. The mint produced U.S. coinage until 1861, when it was taken over by the Confederacy. Confederate coinage was produced there until the end of the Civil War. Operation as a U.S. mint resumed in 1879 and continued until 1909. Between 1932 and 1943, the building was used as a federal prison. In 1966, the building was transferred to the state of Louisiana, and it is now part of the Louisiana State Museum system.

We left the mint and walked deeper into the French Quarter along Royal Street. For a few minutes we stopped near the corner of Toulouse Street to listen to a street band.

For lunch, we found an outside balcony table at Chartres House, reputed to have been a favorite watering hole of Tennessee Williams. The balcony overlooked Chartres Street, and up the street we could see the spires of St. Louis Cathedral at Jackson Square where we had begun our week in New Orleans. We took our time enjoying our lunch of corn and crab bisque and shrimp and chicken jambalaya while memories of our visit to New Orleans drifted through our minds and brought smiles to our faces.

Views: 214

Some other stuff for later,

- 58My wife and I recently returned from a trip that included a two-night stay in Savannah, Georgia. Neither of us had been there before, yet some source deep in memory gave me the notion that we would find a charming, picturesque and historic place. In preparation for our visit to…

- 58Leaving Durango, our road trip’s next destination is Buffalo, Wyoming. Our visit to Buffalo completes a circle, linking this road trip to our last big road trip when we visited the town for the first time and stayed at the Occidental Hotel in 2010. The distance from Durango to Buffalo…

- 58We drive north from Buffalo on I-90. Our destination tonight is the town of Anaconda, about 20 miles west of Butte, Montana. The founder, copper king Marcus Daly, wanted to call the town “Copperopolis,” but another Montana mining town had already claimed the name. So the town became Anaconda instead,…

Leave a Reply